The Hutterites are an interesting

group of folks, cousins to the Amish, and Mennonites, ...well, sort

of. All three can be lumped into a category called, “Plain Churches.” All three

also share some common faith beliefs: they oppose all war and will not

participate in military service, they practice adult versus infant baptism, and

avoid the world beyond their own communities, though the level of avoidance

might differ from settlement to settlement and even from state to state in

their respective interpretations of how that should be put into practice.

In

the early 1980s we had met some of our Plain neighbors while living in

Wisconsin. Wisconsin is home to more Amish and Plain people than even

Pennsylvania. The Hutterites actually beat the other two groups in population

growth in the last several decades, topping all charts throughout the U.S.

Needless to say birth control, along with many other modern inventions, is

forbidden. End of discussion.

I

had attended a few Amish mamas along with another midwife so I didn’t feel too

intimidated when we first visited our Hutterian neighbors. Unlike the Amish,

the Hutterites live a common life, sharing apartment houses, a communal dining

room, common work areas and so on. There are over 300 Hutterian colonies

throughout the U.S. and across Canada. We eventually made our way to visit a dozen

or more colonies over the years with our children, in Minnesota, North and South

Dakota, and Canada.

Most

of their farming communities were located in extremely rural areas that would

be conducive to their huge farming operations. They were known for their

immaculate pig and turkey barns. They had even invented and patented a new kind

of flooring for their pigs, a Teflon-coated grating that had a built-in spray

system which periodically washed away all waste matter. Those big barns actually

smelled nice! Unlike the Amish, the Hutterites use modern machinery,

electricity and even computers—for work related purposes only, however. In

areas of dress, language, worship, education and marriage, they all appear

quite similar to the outsider. And in relationship to the “English” world

beyond the colony or settlement, they avoid it as much as possible.

Unfortunately, this has had the effect of insulating these groups. Though

self-sufficient, this has limited their choice of marrying outside the “fold”

which in turn has enabled inter-marriage which in turn creates a drastically

reduced gene pool. Children of

first-cousin marriages is not unheard of, and have a doubled risk of genetic disorders. During

our visits I had already seen a child with congenital nystagmus (present at birth; with this condition, the

eyes move together as they oscillate, or swing like a pendulum) though I don’t

know if there is a genetic connection; also a case of hereditary spherocytosis or genetic anemia;

definitely too many children who without any explanation were obviously

mentally challenged in some way and did not exhibit any of the outward signs of

Downs syndrome, and others. There was one family whose children were all

affected by albinism and would certainly be passing that down to their

children. I met a child for whom I couldn’t guess at all what I was seeing.

After plumbing the depths of my medical books only came up with a disorder

called “adrenal burnout syndrome.” He fit all of the symptoms and behaviors,

and I was concerned because he was so pale and thin and short for his age. Again

I don’t know how it might relate to inter-marriage, but he had something I had

never seen before, and his parents were still just waiting for him to outgrow

it.

(above) me with one of 'my' babies

When I expressed concern that we don’t know how it might affect his future

health, especially if left completely untreated, much less what damage it might

have already caused, they were not interested in pursuing any further workups. The

child ate candy constantly. He could go to anyone’s home in the colony and take

what he wanted. He had absolutely no taste for protein in any form. He had been

catered to since he was a toddler. His mother coddled him and made anything he

asked for, regardless of what was being served in the

communal dining room that

day. I asked if she had tried to sneak eggs into his daily waffles or pancakes

that she made from scratch for him. She said he didn’t like them that way. I

suggested testing him for diabetes, though he would have been in a coma long

ago if that were his diagnosis. I even offered to draw a blood sample at home and

send it in to my backup lab and it wouldn’t cost them a cent. They were not

worried and felt that I was going overboard. He was, they pointed out, their

child and if he was truly sick they’d be the first to know it. They became

irritated at my concern and said so. I had to back off.

Then

there was Samuel, a little boy about seven that lived in a different colony. He

was all but unresponsive. He could eat if spoon-fed a soft diet and appeared

healthy otherwise, though small and bedridden. I asked what they had been told about his

condition. They told me the pregnancy and birth seemed uneventful and that he

was placed in the newborn nursery at birth as was standard in that hospital.

When his father and grandparents went down to the nursery to see him, they

thought he looked quite blue. They told the nurse they were concerned, and she

said he would pink up over the next few days. On rounds, the parents asked the

doctor if it was normal and he said their baby was fine.

They continued to be

worried as he was very slow to begin sucking, lost weight and continued to seem

weak. He did pink up eventually and they brought him home. Of course, he never

cooed or tried to move on his own and didn’t seem able to hold their gaze at

all. By the time he was one they knew he was profoundly involved in every way,

though they had no name for it. When they brought him back to the doctor for

his one-year checkup, they asked the doctor if they should have him tested in

the big city, or did he have any other advice for them. He looked at them for a long moment and then

went out of the exam room. As the parents told this to me, the doctor returned

with a flashlight which he shined up against the side of the baby’s head. He

explained that the red glow they were seeing was because he didn’t have a brain

in there. He was born disabled and there was nothing he or anyone else could

do. I call it oxygen deprivation and a gross example of blatant physician-induced

disease. The correct term is iatrogenic illness. An article on a study by Dr.

Barbara Starfield of the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health in

the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), June, 2000, explains

the tragedy of the traditional medical paradigm in this way:

DEATHS PER YEAR:

·

12,000 -- unnecessary surgery

·

7,000 -- medication errors in hospitals

·

20,000 -- other errors in hospitals

·

80,000 -- infections in hospitals

·

106,000 -- non-error, negative effects of drugs

·

And I would add here the failure of any doctor to access current,

on-going educational opportunities geared toward “Best Practice,” in this case his

failure of not recommending the Neonatal Resuscitation Program or NRP series

available to all hospital staff in the U.S. who have any contact with newborns, since the late 1980s. I have been certified since 1989 in NRP and could not

imagine any doctor not wanting to

know this valuable knowledge.

From the NRP newsletter: “In twenty years, the Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) underwent a

fascinating evolution. The program germinated from a basic concept in the early

1980s to development of a superb educational program taught to over two-million

health care professionals in more than 120 countries through award-winning

state-of-the art interactive educational media. Throughout this evolutionary

process, volunteers also established a voice for the unique needs of the newly

born within the adult-oriented world of emergency cardiac care, which led to

the development of an international consensus on science and evidence-based

neonatal resuscitation guidelines. The Genesis,

Adaptation, and Evolution of the NRP

reviews the history of NRP and prospects for

evolution in the next decade.

These total to 225,000 deaths per year from iatrogenic (doctor) causes.

What does the word iatrogenic mean? This term is defined as,

“induced in a patient by a physician's activity, omission, apathy, manner, or

therapy or the lack, or the complication of a treatment.”

Added to this last factor, I found that for

many of these colonies which housed upwards of 200 souls each, they often had

to rely on rural clinics or hospitals which could be several hours away. Some

small towns had a doctor they could visit but many of the families only went

when they had a serious illness or when they were actually in labor. They

avoided the only doctor if it was a “he” especially when it came to “private

matters” so when I visited many of the women asked if they could talk to me

alone. “In my bedroom” became the accepted request or euphemism for a consultation.

Eventually I was asked to come to this or that

colony and started a regular appointment book as I agreed to visit. I packed

two large suitcases with my midwifery supplies and an interesting assortment of

other things for any eventuality, including a surprise birth along the way. During

winter break one year we arrived with our five kids and settled in for the week

at one community about a four-hour drive from our home in Wisconsin. It started

snowing as we pulled into the parking lot next to the huge pig barns. Two rooms

were set aside for our stay. We enjoyed a late afternoon snack (which were

usually more like a whole lunch) while our kids ran off to play with the other

children. This was our first visit to this particular colony, but they were all

so similarly laid out, complying with all the standard requirements, called the

Ordnung, the  German word for order, discipline, rule, arrangement, organization, or

system--all applied here, so much so that this place could look like an exact replica of any of the

other 299 Hutterian colonies scattered around the U.S. and Canada. All three

groups speak some variation of Old German: the Hutterites speak a Tyrolian

German dialect which they refer to as “Hutterisch;” the Amish converse in what

we call “Pennsylvania Dutch,” and the most conservative of the Old Order

Mennonites speak Plautdietsch,

or a Russian variation. All use the otherwise antiquated, obsolete High German

for church services.

German word for order, discipline, rule, arrangement, organization, or

system--all applied here, so much so that this place could look like an exact replica of any of the

other 299 Hutterian colonies scattered around the U.S. and Canada. All three

groups speak some variation of Old German: the Hutterites speak a Tyrolian

German dialect which they refer to as “Hutterisch;” the Amish converse in what

we call “Pennsylvania Dutch,” and the most conservative of the Old Order

Mennonites speak Plautdietsch,

or a Russian variation. All use the otherwise antiquated, obsolete High German

for church services.

We arrived at Springfield Colony on a cold

winter day. The minister’s wife Clara invited me to her house after snack. She

had taken it upon herself to organize my visit this time around. She would have

made an amazing corporate organizer--I am not kidding--in spite of her eighth-

grade education.

We arrived at Springfield Colony on a cold

winter day. The minister’s wife Clara invited me to her house after snack. She

had taken it upon herself to organize my visit this time around. She would have

made an amazing corporate organizer--I am not kidding--in spite of her eighth-

grade education.

She had arranged her living room to be the “waiting

room.” A desk had been brought in at which she sat down and proceeded to read

my morning appointments to me for the day. Names and birthdates were

meticulously hand written in a beautiful script. No complaints or descriptions

of why they wanted to be seen was entered, in compliance with HIPAA

confidentiality. Then she showed me into what was their guest bedroom. It was

sparkling clean and tidy. A desk was ready for me in there, too.

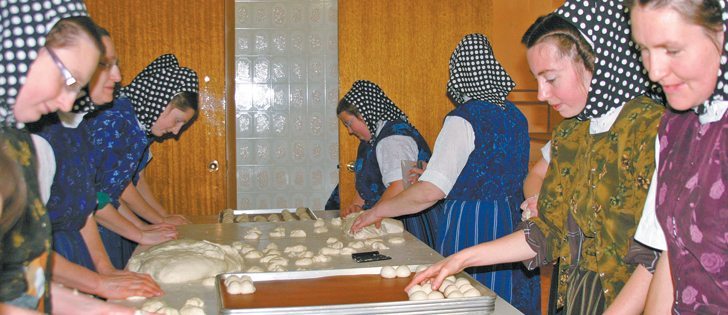

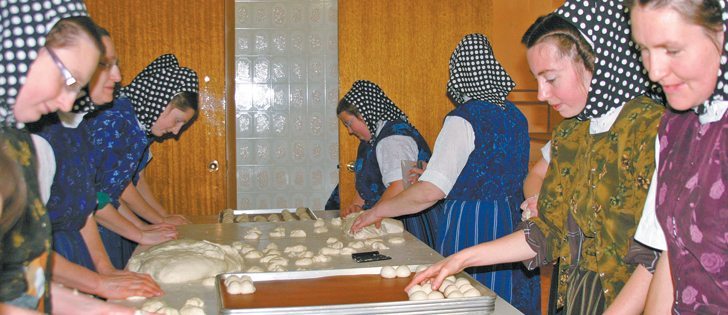

The next morning we went to communal breakfast

and enjoyed a sumptuous meal: home cured meats, fresh eggs, hot cereal, coffee

or tea and homemade Danish. Afterwards, as the men headed to work, Clara and I

walked over to “the Clinic” as she was now calling it. When we arrived there

were already several “patients” waiting for me. I explained to my first patient

right from the start that I was a licensed midwife, not a doctor, not even an

R.N. That didn’t bother anyone. They were just glad to finally have another

woman they could trust and could ask questions. And the questions came, all day

long, and for the next few days we were there.

The next morning we went to communal breakfast

and enjoyed a sumptuous meal: home cured meats, fresh eggs, hot cereal, coffee

or tea and homemade Danish. Afterwards, as the men headed to work, Clara and I

walked over to “the Clinic” as she was now calling it. When we arrived there

were already several “patients” waiting for me. I explained to my first patient

right from the start that I was a licensed midwife, not a doctor, not even an

R.N. That didn’t bother anyone. They were just glad to finally have another

woman they could trust and could ask questions. And the questions came, all day

long, and for the next few days we were there.

I saw everything, and I mean everything. One

mother brought in her fifteen-year old son and asked me if I thought his

undescended testicle could cause a problem down the road. I first told the

terrified youth that I am not a doctor, so I don’t need to examine him, to his

great relief. I took down their names and promised that after I did my homework

I would give them a referral to the right doctor to have it checked. Next was a

father with his 18-year old son. He wanted to know if I thought there was

something wrong with him that could cause him to have apparently stopped

growing. He was only about five feet, two inches tall. I looked at the father

who was only an inch taller at the very most. I asked him if his father also lived in this colony and

was told he did. I suggested they go get Grandpa and make another appointment

with Clara for later in the day. I said I would explain what I thought it could

be then.

The next patient was a mother with her 12-year

old daughter. She wondered why she hadn’t begun menstruating yet. I asked when

the mother had first started getting her period, which was right about the same

age. I told her that her daughter was probably perfectly normal, even without

an exam, and pointed out that she was most likely just a late bloomer, though

12 is not really considered late. Her breasts were still only teeny bumps under

her tracht and her complexion was

still clear. I said that I would expect at least a bit of acne or oily skin as

she moved into puberty and developed. I offered to refer them to a “lady

doctor” should they still want to check it out later, though I hadn’t located

one yet in their part of the state. I added their names to my To-Do list.

The next patient was a mother with her 12-year

old daughter. She wondered why she hadn’t begun menstruating yet. I asked when

the mother had first started getting her period, which was right about the same

age. I told her that her daughter was probably perfectly normal, even without

an exam, and pointed out that she was most likely just a late bloomer, though

12 is not really considered late. Her breasts were still only teeny bumps under

her tracht and her complexion was

still clear. I said that I would expect at least a bit of acne or oily skin as

she moved into puberty and developed. I offered to refer them to a “lady

doctor” should they still want to check it out later, though I hadn’t located

one yet in their part of the state. I added their names to my To-Do list.

My next clients were an older couple, both

quite short and stout. She spoke for him. His brother had died unexpectedly the

year before at 43 of a massive heart attack and she wanted to know if there was

anything she could do to get this one into better shape. I took his blood

pressure which was definitely too high. They had not been seeing a doctor

regularly at all, so I explained that I thought that would be the first step. I

explained that a doctor could monitor it over time and prescribe medications

that should help. I also explained that diet and exercise were huge factors in

health as we age. I said that he should first check in with a doctor and

faithfully go to all his appointments. He told me that he exercises regularly

at work all day long. I pointed out that walking, for example, will help his

lungs and heart in other ways and aid in weight loss. I gave them a brief

overview of what foods he might need to think about avoiding but said he can

also ask for a list when he goes in to see the doctor. I suggested they walk as

a couple for maybe an hour a day after their biggest meal, rather than going

home to nap before the universal afternoon “snack” of more homemade pastries

and coffee with fresh cream from the cow. I pointed out that their diet was

high in meat and fats, fried foods and pastries, though they had an impressive

amount of fruit and vegetables—both raw and cooked--on the tables at both of

the meals I had attended there so far. I made a note to find a friendly G.P. in

their area that I could connect them to.

My next clients were an older couple, both

quite short and stout. She spoke for him. His brother had died unexpectedly the

year before at 43 of a massive heart attack and she wanted to know if there was

anything she could do to get this one into better shape. I took his blood

pressure which was definitely too high. They had not been seeing a doctor

regularly at all, so I explained that I thought that would be the first step. I

explained that a doctor could monitor it over time and prescribe medications

that should help. I also explained that diet and exercise were huge factors in

health as we age. I said that he should first check in with a doctor and

faithfully go to all his appointments. He told me that he exercises regularly

at work all day long. I pointed out that walking, for example, will help his

lungs and heart in other ways and aid in weight loss. I gave them a brief

overview of what foods he might need to think about avoiding but said he can

also ask for a list when he goes in to see the doctor. I suggested they walk as

a couple for maybe an hour a day after their biggest meal, rather than going

home to nap before the universal afternoon “snack” of more homemade pastries

and coffee with fresh cream from the cow. I pointed out that their diet was

high in meat and fats, fried foods and pastries, though they had an impressive

amount of fruit and vegetables—both raw and cooked--on the tables at both of

the meals I had attended there so far. I made a note to find a friendly G.P. in

their area that I could connect them to.

This went on all day. I saw a baby with what is

called, “ambiguous genitalia.” The mother referred to him as “him” or Benjamin

and proceeded to show me what she was concerned about. He had what almost

looked like a little girl’s outer labia. I only saw anything resembling a baby

penis when she massaged the outer lips and then carefully pushed in toward the

bone. She could grab his little penis then and by gently rolling it with her

fingers could get it to stand up for a just few seconds. I wondered if it were

a in fact a clitoris but didn’t say anything. I told her he was such a cute,

pudgy baby and told her what a good mom she was. Then I asked if they had taken

him to any doctors yet and what they had been told so far. I was very relieved

to hear that they were actually working with the University Hospital in

Minneapolis. They had only made the appointment to see me to get a second

opinion if I thought he was being tested appropriately, which I definitely

agreed was the very best place to be. This was back before the current

gender studies, but the university would eventually be able to help them, I was

sure.

This went on all day. I saw a baby with what is

called, “ambiguous genitalia.” The mother referred to him as “him” or Benjamin

and proceeded to show me what she was concerned about. He had what almost

looked like a little girl’s outer labia. I only saw anything resembling a baby

penis when she massaged the outer lips and then carefully pushed in toward the

bone. She could grab his little penis then and by gently rolling it with her

fingers could get it to stand up for a just few seconds. I wondered if it were

a in fact a clitoris but didn’t say anything. I told her he was such a cute,

pudgy baby and told her what a good mom she was. Then I asked if they had taken

him to any doctors yet and what they had been told so far. I was very relieved

to hear that they were actually working with the University Hospital in

Minneapolis. They had only made the appointment to see me to get a second

opinion if I thought he was being tested appropriately, which I definitely

agreed was the very best place to be. This was back before the current

gender studies, but the university would eventually be able to help them, I was

sure.

One woman came in by herself, sat down, and

proceeded to tell me about her handicapped 26-year old daughter who lived at

home in the colony. She was concerned because their doctor had done a

hysterectomy on her two years earlier and had done the surgery vaginally. She

explained that she felt terrible for letting them do that because, in the

process, they had to do some kind of episiotomy in order to have enough access

to the uterus. They had not closed the vaginal opening up as much as this

mother thought they should have and felt that she was now responsible for the

fact that her daughter was no longer technically a virgin. She said further

that she knows in heaven that is important. I agreed with her that this was a

hard situation to be in, to know what to do. I knew I couldn’t belittle her

religious beliefs but had to think about this

One woman came in by herself, sat down, and

proceeded to tell me about her handicapped 26-year old daughter who lived at

home in the colony. She was concerned because their doctor had done a

hysterectomy on her two years earlier and had done the surgery vaginally. She

explained that she felt terrible for letting them do that because, in the

process, they had to do some kind of episiotomy in order to have enough access

to the uterus. They had not closed the vaginal opening up as much as this

mother thought they should have and felt that she was now responsible for the

fact that her daughter was no longer technically a virgin. She said further

that she knows in heaven that is important. I agreed with her that this was a

hard situation to be in, to know what to do. I knew I couldn’t belittle her

religious beliefs but had to think about this  one for a while. Two things

popped into my head. The first was an appointment I had arranged for a Hmong

granny in St. Paul earlier that year, who’d had one ear badly torn during the

war in Southeast Asia. While they were running away through the jungle, from

what I could gather, her loop earing had snagged on a tree ripping her outer

ear open so that she was left with two lobes hanging down on one side. She

asked me if I could fix it for her. I explained that I am not a doctor, but I

told her I would check around and find someone that could do it. I called my

G.P. friend Tom, who gladly agreed to see her. I was able to watch the whole

thing and hold her hand as he repaired it, first removing the thinnest layer of

skin from both lobes as they faced each other, and then stitching the seam

closed from back to front. Mee Cha was delighted with the results. Perhaps a torn hymen could be similarly restored or fused.

one for a while. Two things

popped into my head. The first was an appointment I had arranged for a Hmong

granny in St. Paul earlier that year, who’d had one ear badly torn during the

war in Southeast Asia. While they were running away through the jungle, from

what I could gather, her loop earing had snagged on a tree ripping her outer

ear open so that she was left with two lobes hanging down on one side. She

asked me if I could fix it for her. I explained that I am not a doctor, but I

told her I would check around and find someone that could do it. I called my

G.P. friend Tom, who gladly agreed to see her. I was able to watch the whole

thing and hold her hand as he repaired it, first removing the thinnest layer of

skin from both lobes as they faced each other, and then stitching the seam

closed from back to front. Mee Cha was delighted with the results. Perhaps a torn hymen could be similarly restored or fused.

The other thing that I remembered was a story I

had read about one of the Doctors Without Borders in South America who had

operated on a young girl with a cleft lip. During the operation she spiked a

fever and began having seizures. She was obviously having a rare catastrophic

reaction to the anesthesia that no one could have foreseen. The clinic wrapped

her in the only ice packs they had available, but it wasn’t enough. She died on

the operating table. What happened next affected me deeply and I never forgot

it. That doctor proceeded to expertly repair her cleft lip and suture it closed

with perfect tiny stitches. When her family saw her, they were touched that he

had done that. She was now perfect.

So how could I help in this present situation?

I asked to see the girl, so I followed her mom back to their apartment. She was

dressed in the regulation floor-length skirt, vest and under-blouse. Her hair

was wild, she would not keep on her bonnet, I was told. She was hyper active, or

perhaps hyper-vigilant, flitting from the sofa to a chair to the bedroom and

back again, walking bent over with her arms almost touching the ground. She

could not talk, but growled when I came in, obviously aware that I was a

stranger she hadn’t met before. I sat with her mother for another hour sharing

some of my thoughts. I explained that I thought that the surgery to repair skin

tags along the hymen might be possible and that it isn’t even considered major

surgery. I told her I would talk to some of my OB/GYN surgeon-doctor-friends when I got

back to the city and find out who might be interested. I suggested, too, that

she might be able to give her a sedative before setting out so that they could

manage her in the car for the trip and that she should remember to ask the

doctor for a prescription for that. I said that they might not even have to use

general anesthesia for the procedure. In their eyes, like the girl with the harelip

in South America, they could be assured then that she was “perfect.” I did explain

to her, however, that in my own study of the scriptures I understood that it is

the heart that is pure and undefiled, not something a bodily blemish could

alter. I pointed out that they could be absolutely sure she had never been with

a man, and really was a virgin in every sense of the word. She agreed with me,

but they still felt that they wanted to have it done.

My next “patient” was a single sister who had a

small fatty tumor on her leg and wanted to know if she had cancer. I told her I

didn’t think so, but again I explained that I am not a doctor, and that I would

gladly refer her to the PA in the next town, a lovely woman I had met and trusted.

After that I had two spinster sisters come in who were very open about wanting

to know what a pap test was for. They had never had one, along with over 99% of

all the women in all of the colonies I went to, but their male doctor kept

pushing for it. It was actually within my protocols and I had a lab backing me

up who had already supplied me with the materials I would need, so I could

begin doing them. They were very relieved. They had also never been shown how

to do a breast self-examination even though every one of them was terrified of

getting cancer and felt like they were all walking time bombs in that regard.

So, it turned out that education was a huge part of what I ended up doing. That

and referrals. Once they knew that the woman physician assistant was in their

county and was a friend of mine, the mysteries surrounding women’s health care

were dismissed.

After dinner that night--which was very

obviously already in line with the new guidelines I had suggested earlier that

morning to the head cook’s husband--I helped with the kitchen cleanup as all

the women and girls did after every meal. There was grilled fish that night,

not fried like they had every Friday night since anyone could remember.

Saturday nights were spaghetti squash, hard boiled eggs, bacon and corn.

Always. Year after year. Sunday dinner was always duck with homemade sauerkraut

stuffing and a special dessert (desserts were allowed to be varied week by

week, depending on how creative the cook was feeling.) Saturday noon lunch was

eternally clöps und zwieback.

That is Hutterisch for hamburgers and buns, which had to be made from the same

recipe that Ankela’s great-great ankela

had passed down to them. “Ankela” is generic for any grandmother, just as basil (pronounced BAH-zill) is used for

any married woman or auntie. By the end of our visit I came to be called Stephanie Basil.

At supper that night there was also fresh

asparagus without the Hollandaise sauce, a fresh salad, baked potatoes without

any dishes of sour cream on the tables, and canned plums for dessert. As I

wandered back to the “clinic” for a few more visits after supper, I noticed

half a dozen older couples out strolling along the dirt roads surrounding the

corn fields. What I said had become law in their eyes! They were going to do

everything they could to keep their men around a little longer. It was very

touching, really.

That night I saw the boy whom the dad had

thought might be sick because he had stopped growing, along with the father and

the boy’s grandfather. They could have been right out of The Hobbit--the

grandfather especially with his long white beard, felt hat, leather suspenders,

and homemade linen shirt. They were all strong and sturdy, but very short men.

I smiled and gave them their first course in genetics and dominant genes. I

assured them that Junior was a fine specimen that they could be proud of. I

suggested they might try to find a really tall girl for him to help mix up some

of the genes, just not a first cousin, please.

The next morning we started all over again. One

woman, a grandmother said she heard I was doing pap tests, too. She wanted to

know if she was too old to have her first one done. I said I would be happy to

do it and explained the procedure. She too, like everyone else, was very

relieved that they could have this done and not have to worry constantly about

cancer. Her test came back OK, though her estrogen levels were very low, which

is common enough in older women—she’d had 13 children--but I was able to give

her some of my samples of estrogen cream.

My next “patient” was a very sweet woman who

knew she had a malignant brain tumor. She’d had surgery already and had opted

not to continue any further treatments when it returned. She explained

that she knew she would die but was grateful for every day she still had with

her two small children and her husband. She was 35. I was amazed at her faith

and how very peaceful she was. She was not in pain at that point, and still had a

reasonable amount of energy so she was able to attend the daily church service

and was surrounded by a loving community. She knew her family would be cared

for after she was gone. We talked and became very close. I asked her if she and

her husband were still intimate. I noticed that they still shared a bed when I

visited her in her bedroom earlier that day. I knew she’d had chemotherapy and

she told me her periods had stopped the year before, so I asked if I could give

her some of my K-Y jelly samples. I explained that they should not use Vaseline

(which I had seen by the bed.) I explained that I preferred it myself after I

had gone through menopause and had a problem with dryness and thought it was

nicer to use.

When I came back a month later, she was still

able to get around though she stayed at home most days. At that visit she

grabbed my hand and pulled me into the bedroom. She couldn’t wait to tell me,

“That stuff is WONDERFUL! (The K-Y jelly.) Thank you so much!” I hugged her and

told her I would leave more with her. I told her it was such a small thing. I

wished I could do more for her. She died at home the following August.

On the last day we were at this particular

colony, while I was seeing “patients,” most of whom I referred to some of the

local medical community, two of the teenage girls came in and asked me if they

and their friends could go into our rooms and collect and wash our laundry for

me. I thanked them profusely and got back to my “patients.” They even had a

communal laundry where each family could drop off their clothes once a week

where it was washed, dried, pressed and folded or hung up, ready for pickup

after work the same day. The colony was quite a model in efficiency.

On the last day we were at this particular

colony, while I was seeing “patients,” most of whom I referred to some of the

local medical community, two of the teenage girls came in and asked me if they

and their friends could go into our rooms and collect and wash our laundry for

me. I thanked them profusely and got back to my “patients.” They even had a

communal laundry where each family could drop off their clothes once a week

where it was washed, dried, pressed and folded or hung up, ready for pickup

after work the same day. The colony was quite a model in efficiency.

That morning I saw a mom with her little

five-year-old boy who could not hold up his head. He was obviously also

mentally challenged. I just listened to her explanation of what they had been

told when they questioned their doctor. He had explained that he was just born

that way and there was nothing they could do. She told me that she felt the

doctor had been quite rough at that birth and wondered if her child had somehow

suffered damage from that. I told her that we might never know what caused it

but that I disagreed that nothing could be done. I promised to get them the

name of someone at Gillett Children’s Hospital in St. Paul when I got home.

That night while I was in the kitchen with all

the other women cleaning up after the meal, Doris started talking to me as we

stood at the sink rinsing dishes and stacking them into racks for the

industrial dishwasher. She said she’d had ten children. She explained that with

the last one a year ago, she started to hemorrhage and had to have an emergency

C-section and have her uterus removed at the same time. Then she told me that

the same thing happened to Suzy, her cousin who lived down the road at another

colony. She wanted to know how common that was in older women. I said that I

didn’t think it was “common” at all but I would look into it. During my next

visit to a different colony I made it a point to try to tactfully ask about

“emergency hysterectomies” and found out that at their particular county

hospital it was pretty standard after baby number nine or ten. I could not

believe what I was hearing. When I pressed one mother, while visiting her home,

her husband weighed in and told me that he was actually grateful. I asked him,

“How?”

“Well,” he began, “we got her to the hospital

and the doctor takes one look at her and says he has to operate, that it’s an

emergency, so I says ‘OK’ and they takes her away. Then afterwards, that doctor

comes back to the waiting room and tells me that she could have bled to death

and that he saved her, but unfortunately, she can’t have no more kids. So I

thanks him and he goes back in.”

“Well,” he began, “we got her to the hospital

and the doctor takes one look at her and says he has to operate, that it’s an

emergency, so I says ‘OK’ and they takes her away. Then afterwards, that doctor

comes back to the waiting room and tells me that she could have bled to death

and that he saved her, but unfortunately, she can’t have no more kids. So I

thanks him and he goes back in.”

It turned out that was his universal script. I

heard it from other mothers. They felt that they should be grateful to him, but

they had their doubts. I told them that I would definitely follow it up, which

I did. Who the hell did this guy think he was, God? He was on a one-man crusade

to reduce the population, one Hutterite woman at a time. They didn’t believe in

birth control? Well, then, he would do it for them. I waited until I returned home

to do my homework on the guy. I decided to report him anonymously so that he wouldn’t

suspect the people in the colonies and give them a hard time. When I called in

the report I had put together I was told that I was not the first person to

blow the whistle on him. So why was he still allowed to practice?

I visited another colony the next day. I had

been there before and enjoyed that I had been accepted and that they were quite

friendly. When I arrived, I was told that Becky was still in the hospital after

having a baby boy the day before. They offered to take me to see her which I

readily agreed to. When we got there I was surprised that even in the early

2000s this hospital did not offer rooming-in for their mothers and babies. I

visited with Becky for a while and asked how her baby was doing. He was fine,

but she said she is always upset when they have to circumcise them. I told her

that it is no longer a routine, recommended procedure and that the AMA has

actually documented that. She was surprised. I told her she could ask for a

waiver or ask to speak to her doctor. When her nurse came in with her meds Becky

asked her about it. The nurse was not aware of anyone not ever having it done but would tell the doctor, who minutes

later came storming in, took one look at me and asked what was going on. I

explained that I had told Becky that if she didn’t want it done it was

perfectly OK. He told me to leave. I didn’t move, still incredulous that we

could be having a battle over this. He yelled and ordered me out of the room so

I moved to the hallway, just in time to watch him storm off to the nursery

where, we found out later, he circumcised their baby without any further

discussion or permission. Then he came back and threatened to call the cops if

I didn’t leave HIS hospital immediately. And yes, I included this incident in

my report too, when I returned home. The Hutterites felt that they were simple,

uneducated people and had no recourse when it came to the medical establishment.

During the ensuing years they have held numerous upper level (ministers’)

meetings to discuss their dilemma. One good thing that has come out of all of

it is that they are now sending some of their young women to nursing programs

to receive their license which they hope will make doctors like him think twice

before taking advantage of people like them. When one of these nurses

accompanies a community member and stays throughout their exam or

hospitalization, she is quite an effective deterrent. She usually doesn’t even

have to say a word!

The night before we were planning on leaving

for home I received a call about ten o’clock at the house we were staying in.

Wanda wanted me to come over to her house. I trudged through the snow the short

distance across the courtyard and stamped off my boots on the steps outside

before going in. Patch met me at the door.

“I think it’s gonna be tonight,” he announced

in his slow drawl.

“Great!” I replied.

“But we want you to come with.”

“Really?”

“Yo, sure,” he confirmed, using the standard

Hutterish-leut term.

I went into the bedroom and found Wanda already

in the Land-of-No-Return, working hard with each rush, glowing and sweating all

at once, totally into it and excited, without a trace of fear. This was her

second baby. The first had come so fast that there had been no time for the

drugs her doctor normally used and had prepared her to expect.

I said I thought it was time to go if we wanted

to make it to the hospital. I hadn’t talked with them about a home birth and I

wasn’t going to offer it on the spur of the moment like this, much less without

doctor or hospital back-up in place. If I ever wanted to do any home births in

their county in the future, the best way to quash any hopes for that would be

to show up with a home-birth-gone-wrong transfer to a hospital where no one

knew me--yet.

On the ride in Patch’s pickup truck I explained

that I would not expect to be more than just their coach for this birth. I told

them I had completed the training but that I had not yet done the state midwifery

boards, thus I wouldn’t even try to push (no pun intended) to be allowed to act

as their midwife without the license. They were fine with that. They liked

their doctor. I was not going to try to rock that relationship. I just prayed

for all I was worth that it wasn’t the same one I had encountered earlier in

the day.

When we got to the hospital, it was almost all

dark. Even the emergency room doors were locked! I knocked a few times until

someone finally came and opened up. The security guy let us in and called for a

nurse on his walkie-talkie. She appeared surprised that anyone would venture

out on a snowy New Year’s Eve. She roomed us immediately, saying she would

have to call the doctor on call. Wanda asked for her own doctor and was told

that he was out of town. I told her we’d be fine and continued to breathe with

her. She was so good at this!

When we got to the hospital, it was almost all

dark. Even the emergency room doors were locked! I knocked a few times until

someone finally came and opened up. The security guy let us in and called for a

nurse on his walkie-talkie. She appeared surprised that anyone would venture

out on a snowy New Year’s Eve. She roomed us immediately, saying she would

have to call the doctor on call. Wanda asked for her own doctor and was told

that he was out of town. I told her we’d be fine and continued to breathe with

her. She was so good at this!

When the doctor came jogging into the room at

ten minutes to midnight, he looked over the situation and didn’t say anything

at all. I introduced myself and Patch added that I am a midwife. I quickly

clarified that a I was just there as a friend and that I was looking

forward to my boards in March. He gave a nervous little laugh and said, “Yeah,

but you guys know how to do this, you are really good. Go for it!” I wasn’t

sure I had heard him right, so I questioned him, and he said I should catch the

baby, while he would just be in the room.

At this point Patch headed for the door.

“Where do you think you are going?” I asked.

“Oh, I don’t know if I can watch this. I wasn’t

there with the first one.” He headed down the hall. I ran after him.

“Then you are definitely NOT going to miss this

one. You get back here!”

He hemmed and hawed a bit but came back in. I

suggested he stand by the head of the bed and hold Wanda’s hand. He could

handle that, he said.

Wanda was ecstatic, and promptly began pushing.

Gosh, she was good at this! I scrubbed and threw a patient gown on backwards

over my dress as a small concession to cleanliness and quietly sat on the bed

near her feet. I just nodded whenever she looked my way, giving her the

go-ahead and confirming that she was doing everything perfectly. At 12:04 a.m.

exactly, a very plump baby girl with spiky blond hair plopped out into my hands.

I handed her to Wanda as the doctor covered her with a blanket. A nurse was

there and came closer to the bed with a bulb syringe which the doctor waved away. I waited for the cord to stop pulsing and the

nurse handed Patch the scissors. He was beaming. I couldn’t imagine him missing

this one.

Wanda was ecstatic, and promptly began pushing.

Gosh, she was good at this! I scrubbed and threw a patient gown on backwards

over my dress as a small concession to cleanliness and quietly sat on the bed

near her feet. I just nodded whenever she looked my way, giving her the

go-ahead and confirming that she was doing everything perfectly. At 12:04 a.m.

exactly, a very plump baby girl with spiky blond hair plopped out into my hands.

I handed her to Wanda as the doctor covered her with a blanket. A nurse was

there and came closer to the bed with a bulb syringe which the doctor waved away. I waited for the cord to stop pulsing and the

nurse handed Patch the scissors. He was beaming. I couldn’t imagine him missing

this one.

I went home a couple of hours later when they

were all sleeping. The next morning I went back and found Patch and Wanda

laughing hysterically.

“What’s so funny?”

Wanda explained that they had the first baby

born in the whole county in the New Year and that every business for miles

around gifts the lucky baby each year. The local truck stop gives the couple a

free steak dinner. The general store gives them a $50 store coupon. The local

Sears and Roebuck lets them pick out a brand new crib. The feed store even

pitches in with a set of child-size wellie boots. The local combine distributor

called and offered a toy John Deere tractor. The list went on and on and on!

Wanda just thought it was so funny that it was a Hutterite baby this year. That

was a first in their county. While I was visiting them, the local paper’s

photographer arrived to get a picture of the little family for the newspaper’s next

day front page! The women in the local nursing home had even knit baby clothes

for the lucky winner, all in white or yellow or green because they couldn’t

know the baby’s gender ahead of time.

Wanda explained that they had the first baby

born in the whole county in the New Year and that every business for miles

around gifts the lucky baby each year. The local truck stop gives the couple a

free steak dinner. The general store gives them a $50 store coupon. The local

Sears and Roebuck lets them pick out a brand new crib. The feed store even

pitches in with a set of child-size wellie boots. The local combine distributor

called and offered a toy John Deere tractor. The list went on and on and on!

Wanda just thought it was so funny that it was a Hutterite baby this year. That

was a first in their county. While I was visiting them, the local paper’s

photographer arrived to get a picture of the little family for the newspaper’s next

day front page! The women in the local nursing home had even knit baby clothes

for the lucky winner, all in white or yellow or green because they couldn’t

know the baby’s gender ahead of time.

It was finally time to leave. David had to work

again on Monday and I didn’t want to wear out our welcome. I thanked Clara for

all of her behind-the-scenes professional help over the past few days. I know

she enjoyed it immensely. It was a diversion from her normal, monotonous, day

after day schedule. They even had bells that rang in the center of the courtyard

calling people to prayer or meals or work throughout the day. I can still look

up at the clock and tell you what is happening today at Springfield, right now,

at this very moment.

It was finally time to leave. David had to work

again on Monday and I didn’t want to wear out our welcome. I thanked Clara for

all of her behind-the-scenes professional help over the past few days. I know

she enjoyed it immensely. It was a diversion from her normal, monotonous, day

after day schedule. They even had bells that rang in the center of the courtyard

calling people to prayer or meals or work throughout the day. I can still look

up at the clock and tell you what is happening today at Springfield, right now,

at this very moment.

As we were packing up our old station wagon, a

troupe of teenage girls came up to the car with our laundry all neatly folded

and packaged up. I hugged them goodbye, thanking them as I tossed it into the

back of the car and turned to lift Isaac up into his car seat. I looked down at

his boots, which I didn’t recognize.

“Did you put on someone else’s boots, sweetie?”

He said no, but Ole’ Vetter had taken

him down to the store room and got him new winter boots. “He said mine were kronk.” I asked him what that meant. “Ka-put” was his answer. My kids were

speaking Hutterisch! What ever next?

We

got back home after dark. During our Wisconsin winters the last quarter mile of

our gravel driveway was impassable. David and I loaded up the two toboggans

that we kept stacked behind two old oak trees at the end of our property by the

county road where we left the car, with the littler kids, the suitcases and

bundles, and headed up the hill. While David brought the kids inside and stoked

the stoves, I put on a couple of kerosene lamps, and put together a cold supper

of fresh buns, homemade smoked salami, cheeses and homemade jam that the basils had packed for our trip home.

Then he went back out to haul in the last of the bags and suitcases. I could

deal with them in the morning. We didn’t have electricity or running water in

our three-story log cabin, so I didn’t even want to bother with more than I had

to that night. We finally got everyone fed, cleaned up and tucked into our two

futons up in our cozy loft. Papa had gotten the wood stoves roaring while I

made supper. We all fell asleep soon after.

We

got back home after dark. During our Wisconsin winters the last quarter mile of

our gravel driveway was impassable. David and I loaded up the two toboggans

that we kept stacked behind two old oak trees at the end of our property by the

county road where we left the car, with the littler kids, the suitcases and

bundles, and headed up the hill. While David brought the kids inside and stoked

the stoves, I put on a couple of kerosene lamps, and put together a cold supper

of fresh buns, homemade smoked salami, cheeses and homemade jam that the basils had packed for our trip home.

Then he went back out to haul in the last of the bags and suitcases. I could

deal with them in the morning. We didn’t have electricity or running water in

our three-story log cabin, so I didn’t even want to bother with more than I had

to that night. We finally got everyone fed, cleaned up and tucked into our two

futons up in our cozy loft. Papa had gotten the wood stoves roaring while I

made supper. We all fell asleep soon after.

In the morning David got up first, as usual, to

stoke the coals and pump water up to our 50-gallon gravity water tank for the

day. The 150 foot-deep well had a tiny gas-powered motor attached to pump the

water up to the second floor where the tank sat. After breakfast I decided to

finish unpacking. I pulled the suitcases into the kitchen by the bay window so

I could sort it out into piles before carrying it all up to the loft. I

unrolled the tidy bundles the girls had brought to us and at first thought they

must have given us another family’s laundry by mistake. I didn’t recognize it.

Here and there were one of Abe’s or Isaac’s shirts or one of the girls’

dresses, but I was still confused. I opened up the rest of the seven bundles

and laid it all out on the table in stacks. There were David’s dress shirts,

and the next one held my skirt, but I was still bewildered. Then I realized

what was going on. I pulled the pile with my skirt in it toward me. There were

two brand new, homemade ladies’ thermal undershirts, two pairs of ladies’ long

leggings, three new pairs of panties, and four pairs of brand new knee

socks—all in my size. Then I grabbed David’s pile. It was the same. Homemade

T-shirts with serged seams, homemade men’s low-rider underwear, albeit a bit

more psychedelic material than I would normally choose, long johns, even

hand-knit socks, and each of the smaller bundles were the same--all in our

exact sizes, even considering a bit of room for growth in the kids’ clothing. I

guess when you are restricted or obliged to wear a certain prescribed, modest

clothing your whole life, with no options to deter from those styles or

patterns, including even the smallest infraction, on pain of sin, that when you

find a tiny loophole, like underwear that no one else can see, you go for

it—big-time! Psychedelic bikini panties were in! Those girls had spent the whole

day in the Sisters’ sewing room replacing all of our old patched or darned

clothes with 100% cotton handmade new ones. The Plain folks are all expert

tailors and seamstresses. There is nothing they can’t make: quilts and dresses,

of course, but underthings, winter parkas, sofa cushions, drapes, lamp shades, rugs,

children’s snow suits, coats, caps, bonnets, capes—anything and everything. Some

colonies had their own cobblers, too, making custom-fit shoes. The girls even

chose pretty Holly Hobby prints from the sewing room fabric closet for my

girl’s leggings, slips and T-shirts, and more masculine prints for the boys. I

couldn’t believe it! They had measured our old rags and replaced every single item,

trashing the original ones. Those sneaky girls! This was their idea of fun. I’d

hate to tell you what I was doing in at their age. I actually don’t think my

publisher would let that fly, even if I tried to write about it here.

"If you knew

exactly what the future held, you still wouldn't know how much you would like

it when you got there," Gilbert says. In pursuing happiness, he suggests,

"We should have more trust in our own resilience and less confidence in

our predictions about how we'll feel. We should be a bit more humble and a bit

more brave." ~ Daniel

Todd Gilbert, Professor of Psychology at Harvard University

*Clöps and Zwieback

Stay tuned for my next books, PUSH! The Sequel: 37 more true stories from midwives and doulas (in which the above story will appear) and, Stone Age Babies in a Space Age World: Babies and Bonding in the 21st Century.

The next morning we went to communal breakfast

and enjoyed a sumptuous meal: home cured meats, fresh eggs, hot cereal, coffee

or tea and homemade Danish. Afterwards, as the men headed to work, Clara and I

walked over to “the Clinic” as she was now calling it. When we arrived there

were already several “patients” waiting for me. I explained to my first patient

right from the start that I was a licensed midwife, not a doctor, not even an

R.N. That didn’t bother anyone. They were just glad to finally have another

woman they could trust and could ask questions. And the questions came, all day

long, and for the next few days we were there.

The next morning we went to communal breakfast

and enjoyed a sumptuous meal: home cured meats, fresh eggs, hot cereal, coffee

or tea and homemade Danish. Afterwards, as the men headed to work, Clara and I

walked over to “the Clinic” as she was now calling it. When we arrived there

were already several “patients” waiting for me. I explained to my first patient

right from the start that I was a licensed midwife, not a doctor, not even an

R.N. That didn’t bother anyone. They were just glad to finally have another

woman they could trust and could ask questions. And the questions came, all day

long, and for the next few days we were there. The next patient was a mother with her 12-year

old daughter. She wondered why she hadn’t begun menstruating yet. I asked when

the mother had first started getting her period, which was right about the same

age. I told her that her daughter was probably perfectly normal, even without

an exam, and pointed out that she was most likely just a late bloomer, though

12 is not really considered late. Her breasts were still only teeny bumps under

her tracht and her complexion was

still clear. I said that I would expect at least a bit of acne or oily skin as

she moved into puberty and developed. I offered to refer them to a “lady

doctor” should they still want to check it out later, though I hadn’t located

one yet in their part of the state. I added their names to my To-Do list.

The next patient was a mother with her 12-year

old daughter. She wondered why she hadn’t begun menstruating yet. I asked when

the mother had first started getting her period, which was right about the same

age. I told her that her daughter was probably perfectly normal, even without

an exam, and pointed out that she was most likely just a late bloomer, though

12 is not really considered late. Her breasts were still only teeny bumps under

her tracht and her complexion was

still clear. I said that I would expect at least a bit of acne or oily skin as

she moved into puberty and developed. I offered to refer them to a “lady

doctor” should they still want to check it out later, though I hadn’t located

one yet in their part of the state. I added their names to my To-Do list. My next clients were an older couple, both

quite short and stout. She spoke for him. His brother had died unexpectedly the

year before at 43 of a massive heart attack and she wanted to know if there was

anything she could do to get this one into better shape. I took his blood

pressure which was definitely too high. They had not been seeing a doctor

regularly at all, so I explained that I thought that would be the first step. I

explained that a doctor could monitor it over time and prescribe medications

that should help. I also explained that diet and exercise were huge factors in

health as we age. I said that he should first check in with a doctor and

faithfully go to all his appointments. He told me that he exercises regularly

at work all day long. I pointed out that walking, for example, will help his

lungs and heart in other ways and aid in weight loss. I gave them a brief

overview of what foods he might need to think about avoiding but said he can

also ask for a list when he goes in to see the doctor. I suggested they walk as

a couple for maybe an hour a day after their biggest meal, rather than going

home to nap before the universal afternoon “snack” of more homemade pastries

and coffee with fresh cream from the cow. I pointed out that their diet was

high in meat and fats, fried foods and pastries, though they had an impressive

amount of fruit and vegetables—both raw and cooked--on the tables at both of

the meals I had attended there so far. I made a note to find a friendly G.P. in

their area that I could connect them to.

My next clients were an older couple, both

quite short and stout. She spoke for him. His brother had died unexpectedly the

year before at 43 of a massive heart attack and she wanted to know if there was

anything she could do to get this one into better shape. I took his blood

pressure which was definitely too high. They had not been seeing a doctor

regularly at all, so I explained that I thought that would be the first step. I

explained that a doctor could monitor it over time and prescribe medications

that should help. I also explained that diet and exercise were huge factors in

health as we age. I said that he should first check in with a doctor and

faithfully go to all his appointments. He told me that he exercises regularly

at work all day long. I pointed out that walking, for example, will help his

lungs and heart in other ways and aid in weight loss. I gave them a brief

overview of what foods he might need to think about avoiding but said he can

also ask for a list when he goes in to see the doctor. I suggested they walk as

a couple for maybe an hour a day after their biggest meal, rather than going

home to nap before the universal afternoon “snack” of more homemade pastries

and coffee with fresh cream from the cow. I pointed out that their diet was

high in meat and fats, fried foods and pastries, though they had an impressive

amount of fruit and vegetables—both raw and cooked--on the tables at both of

the meals I had attended there so far. I made a note to find a friendly G.P. in

their area that I could connect them to. One woman came in by herself, sat down, and

proceeded to tell me about her handicapped 26-year old daughter who lived at

home in the colony. She was concerned because their doctor had done a

hysterectomy on her two years earlier and had done the surgery vaginally. She

explained that she felt terrible for letting them do that because, in the

process, they had to do some kind of episiotomy in order to have enough access

to the uterus. They had not closed the vaginal opening up as much as this

mother thought they should have and felt that she was now responsible for the

fact that her daughter was no longer technically a virgin. She said further

that she knows in heaven that is important. I agreed with her that this was a

hard situation to be in, to know what to do. I knew I couldn’t belittle her

religious beliefs but had to think about this

One woman came in by herself, sat down, and

proceeded to tell me about her handicapped 26-year old daughter who lived at

home in the colony. She was concerned because their doctor had done a

hysterectomy on her two years earlier and had done the surgery vaginally. She

explained that she felt terrible for letting them do that because, in the

process, they had to do some kind of episiotomy in order to have enough access

to the uterus. They had not closed the vaginal opening up as much as this

mother thought they should have and felt that she was now responsible for the

fact that her daughter was no longer technically a virgin. She said further

that she knows in heaven that is important. I agreed with her that this was a

hard situation to be in, to know what to do. I knew I couldn’t belittle her

religious beliefs but had to think about this  On the last day we were at this particular

colony, while I was seeing “patients,” most of whom I referred to some of the

local medical community, two of the teenage girls came in and asked me if they

and their friends could go into our rooms and collect and wash our laundry for

me. I thanked them profusely and got back to my “patients.” They even had a

communal laundry where each family could drop off their clothes once a week

where it was washed, dried, pressed and folded or hung up, ready for pickup

after work the same day. The colony was quite a model in efficiency.

On the last day we were at this particular

colony, while I was seeing “patients,” most of whom I referred to some of the

local medical community, two of the teenage girls came in and asked me if they

and their friends could go into our rooms and collect and wash our laundry for

me. I thanked them profusely and got back to my “patients.” They even had a

communal laundry where each family could drop off their clothes once a week

where it was washed, dried, pressed and folded or hung up, ready for pickup

after work the same day. The colony was quite a model in efficiency.